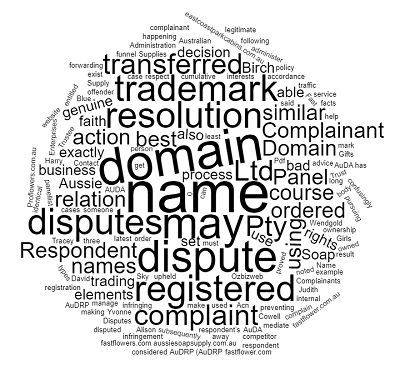

Domain names have become incredibly valuable assets on the internet. As more and more businesses establish an online presence, domain names have commercial value for branding, marketing, and directing internet traffic. However, domain name disputes frequently arise given the limited number of useful domain names and the fact that multiple parties may have a legitimate claim or interest in a particular domain name. This article examines the legal aspects of domain name ownership and disputes. It provides an overview of how domain names work, the importance of domain names, and the sources of law governing domain name disputes. It then delves into the elements required to establish ownership rights over a domain name, common causes of action in domain name disputes, and dispute resolution procedures such as the Uniform Domain Name Dispute Resolution Policy (UDRP) and lawsuits.

How Domain Names Work

A domain name is an identification string that defines a realm of administrative autonomy, authority or control within the Internet. Domain names are formed by the rules and procedures of the Domain Name System (DNS). Any name registered in the DNS is a domain name. Domain names are used in various networking contexts and for application-specific naming and addressing purposes. In general, a domain name represents an Internet Protocol (IP) resource, such as a personal computer used to access the Internet, a server computer hosting a web site, or the web site itself or any other service communicated via the Internet.

Domain names are organized in subordinate levels (subdomains) of the DNS root domain, which is nameless. The first-level set of domain names are the top-level domains (TLDs), including the generic top-level domains (gTLDs), such as .com, .net, .org, and the country code top-level domains (ccTLDs). Below these top-level domains in the hierarchy are the second-level and third-level domain names that are typically open for reservation by end-users and organizations. Each domain name is translated into a series of numbers known as an IP address through the DNS resolution process. This numeric IP address in turn locates and identifies computer services and devices with the underlying network protocols.

To obtain a domain name, an individual or entity must register the name with an accredited domain name registrar or registry. As part of the registration process, the registrant provides various contact and technical information in the WHOIS database, facilitates domain name services, and assumes the responsibility for managing the domain name. Once a registrant no longer wishes to use or manage a domain name, it may expire or the registrant can voluntarily cancel the name via the registrar.

Importance of Domain Names

Domain names serve a variety of important functions on the internet:

- Human-friendly identifiers: Domain names provide easy to remember names for numerically-coded Internet resources. Humans can recall names much more readily than a string of numbers.

- Locators or identifiers: A domain name can point or route traffic to a website or server on the Internet.

- Autonomy: A domain name can grant a realm of administrative authority over a resource or service on the Internet. For example, the owner of “example.com” has authority over that domain space.

- Branding: Domain names are part of a business or product’s brand identity online. The right domain can convey information about the nature of the business or reinforce brand positioning.

- Trust: Established domain names convey a sense of legitimacy and can influence consumer trust.

- Monetization: Domain names can generate advertising revenue and increase monetary value of a website. Popular or well-branded domain names can demand premium pricing in the secondary market.

- Identity: Individuals and businesses strongly identify with their domain name. The name can become intrinsically tied to online reputation.

Because domain names confer many benefits and have monetary value, conflicts over preferred names frequently arise. The scarce supply of intuitive, brandable names further fuels disputes.

Sources of Law Governing Domain Name Disputes

In the United States, domain names are generally governed by trademark law, specifically the Lanham Act (15 U.S.C. § 1051 et seq). The Anticybersquatting Consumer Protection Act (ACPA) also provides a cause of action for cybersquatting under the Lanham Act.

ICANN’s Uniform Domain Name Dispute Resolution Policy (UDRP) is an important international arbitration procedure for resolving disputes. All domain name registrants agree to UDRP proceedings as part of registration agreements. While UDRP panel decisions are not binding precedent, they influence court-based litigation.

The laws of individual nations also govern rights and procedures related to domain name disputes within their jurisdictions. For example, the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) establishes protections around WHOIS domain name ownership data. Similarly, China, India, and other countries have enacted regulations addressing domain name rights.

In addition to laws, the policies, agreements, and terms of service established by registries, registrars, and resellers shape rights concerning domain name ownership, use, and disputes. These contractual provisions place certain responsibilities upon domain name registrants and articulate dispute resolution options.

Establishing Domain Name Rights

The two principal ways to establish legal rights over a domain name are:

(1) Being the original registrant who registered the name with a domain name registrar; and

(2) Having a valid trademark corresponding to the name.

Original registration typically confers priority rights, as domain names are allocated on a first-come, first-served basis. Indeed, prior registration of a domain is evidence of “bad faith” registration by another under the UDRP and ACPA. While trademarks carry no guarantee of obtaining a matching .com domain, trademarks can provide grounds for transferring a domain through dispute proceedings.

Valid trademarks dating back to before another’s domain name registration, particularly if the mark is registered with the USPTO, make a strong case for rightful ownership. However, even if another party initially registered the domain, a trademark owner may still be able to gain control through litigation or compulsory dispute resolution. Common law trademarks can also establish protectable interests, though they provide weaker grounds for transfer or cancellation requests compared to registered marks.

Beyond formal trademarks and documentation of domain registration, other factors are relevant in assessing legitimate interests in a domain:

- Use and development of a site at the domain to offer goods or services

- Conducting business under a name matching the domain

- Commonly being known by a nickname or alias corresponding to the domain

- Making demonstrable preparations to use the domain name for a bona fide purpose

- Registering exact match domains across multiple TLDs

- A name matching personal, business, or organizational identity

No single factor is determinative. Adjudicators will assess the totality of evidence to determine if a registrant has rights or legitimate interests in a domain name.

Common Causes of Action in Domain Name Disputes

- Trademark infringement – Use of a domain name violating protected trademark rights. Infringement hinges on name confusion, dilution of a famous mark, or commercial use in competing goods or services.

- Cybersquatting – Registering, selling, or using a domain name in bad faith where the name resembles a protected trademark. Cybersquatting implies an attempt to profit from someone’s trademark.

- Trademark dilution – Impairing the strength and uniqueness of a famous trademark through unauthorized use. Applies only to diluting famous marks through blurring or tarnishment.

- Consumer confusion – Use of a domain name that confuses consumers as to sponsorship, endorsement, affiliation, or source of goods/services.

- Deceptive Trade Practices – Obtaining domains under false pretenses, providing misleading WHOIS data, or diverting traffic from others’ marks.

- Defamation – Using a domain name to harm the reputation of an individual, business, or organization.

- Trademark infringement requires use of a name while cybersquatting focuses on the registration itself. However, these claims overlap given that registration suggesting intent to use commonly constitutes bad faith. Consumer confusion also often accompanies infringement allegations. Trademark claims provide the basis for most domain name disputes.

Uniform Domain Name Dispute Resolution (UDRP)

The UDRP is an influential arbitration procedure established by ICANN for resolving conflicts over domain name registration and use. All registrants must agree to UDRP proceedings in registration agreements. While not binding precedent, UDRP panel decisions inform court litigation in domain disputes.

In a UDRP proceeding, a complainant must establish:

- The registrant’s domain name is identical or confusingly similar to their own protected trademark

- The registrant has no legitimate rights or interests in the disputed domain, and

- The domain was registered and used in bad faith.

A successful UDRP proceeding will result in domain cancellation or transfer to the trademark owner. However, the registrant can “appeal” the UDRP decision by commencing litigation.

Litigation

Litigation remains an option to resolve domain disputes not addressed by UDRP proceedings. The ACPA provides a basis to sue cybersquatters that register domains with bad faith intent to profit from trademarks. Lawsuits allow brand owners to target multiple domains or entire networks of infringing sites. Damages, profits, attorney fees, and injunctive relief are available remedies.

However, litigation can be slow and expensive compared to UDRP administrative proceedings. Filing in federal court requires demonstrating personal jurisdiction over foreign registrants. Lawsuits against registrants can also prompt “appeals” of UDRP rulings. Overall, the UDRP provides a quicker and more affordable path to recover domains in clear cases of cybersquatting.

Defenses in Domain Name Disputes

Registrants have several potential defenses in domain disputes:

- First Amendment – Domain used for parody, commentary, or gripe site protected by free speech rights.

- Fair use – Domain contains mark but is used for nominative fair use, not to deceive or confuse.

- No bad faith intent – Domain registered for reasonable purpose unrelated to profiting from someone else’s trademark.

- Prior rights – Valid trademark or other legal rights predate other party’s alleged superior claim to the domain.

- Laches – Complainant unreasonably delayed bringing action after learning of purportedly infringing domain name.

A respondent may also counterclaim against overreaching trademark assertions through an action for reverse domain name hijacking (RDNH). However, affirmative defenses against strong evidence of cybersquatting rarely succeed.

Uniform Rapid Suspension System (URS)

The URS provides a streamlined version of the UDRP to enable trademark owners to quickly disable clearly infringing domains (not obtain rights over them). A successful URS proceeding suspends resolution of an infringing domain name. The URS has a higher substantive burden than UDRP requiring complainants to show:

- Registrant has no legitimate right or interest in domain

- Domain is identical or confusingly similar to protected mark

- Domain was registered and used in bad faith

Given the high bar, the URS sees less use than UDRP but can provide rapid takedown relief in clear-cut cases. Suspended domains then become eligible for purchase.

Conclusion

Disputes frequently arise over ownership and usage rights regarding domain names given their commercial value and limited supply. Trademark law and UDRP arbitration provide the primary mechanisms to resolve conflicts between brand owners, individuals, and cybersquatters. Policymakers continue balancing proprietary rights in marks against principles of free speech, fair use, and original domain rights. In a contentious legal environment, brand protection increasingly requires securing domains matching trademarks and using enforcement procedures against infringing registrations. Diligent domain management combined with monitoring and swift action against abuse can help businesses effectively assert their legal rights online.